- Home

- Parker Posey

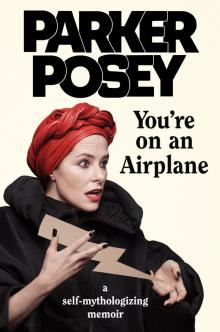

You're on an Airplane Page 4

You're on an Airplane Read online

Page 4

Granny was the bohemian in the family, with relatives from the Netherlands. “Bohemian” was how my parents explained why Granny had no interest in doing things like decorating or cooking or cleaning. She was diametrically opposed to Nonnie, who wallpapered even the light switches to match the walls and did her sewing on a sewing machine. Granny sewed by hand and painted with watercolors—flowers like irises and tulips. She liked her “stories,” which is what we called soap operas back then, and the beauty pageants. She appreciated beauty without having to own it herself.

Before all this, when my dad was a boy, she was a CPA for an accounting firm called Frost and Frost. She wore Andrew Geller shoes and a fur collar and went to work decked out and ready for business. Once she flew to Mobile, Alabama, to set up the books for the branch’s office and when she passed above them in an airplane, my dad and his older sister Peggy waved to her in the air. Peggy was in kindergarten and my dad was around two or three then.

Dad and Peggy had older siblings that they weren’t as close to (they were really wild), and a housekeeper—“maids,” they were called back then—named Mary Baker. She was at the Poseys’ almost all the time. Mary’s husband drove a cement mixing truck and once in a while, if he was in the neighborhood, he would dump a little pile of cement for them to sign their names in. She looked after them as best she could and was a great cook—she made things like chitlins and corn bread and collard greens with ham hocks.

The Bakers’ home was a small shack, located in what was called “the Quarters,” which was made up of dirt roads. You’d park on the paved street to walk into the neighborhood. My dad was born at night, and Peggy remembers walking to the Bakers’ house with my grandfather. Paw Paw entered the house yelling, “Mary Baker! Get your party shoes on! There’s gonna be dancing tonight!” He took them both back to the Posey house, where Dad was born and the next day was circumcised on a card table in the living room.

All the kids had a Red Ryder BB gun back then, according to my aunt Peggy. Once, when my dad was five or six, he was taking the heat off his Fireball jawbreaker under the water faucet in the bathroom. Peggy remembers hearing him hum a song as she stood in the kitchen. She called out to him, taunting and singsongy, “I’m going to shoot you . . . right between the eyes!” When he came out of the bathroom, there was Peggy, about twenty feet away, pointing her Red Ryder BB gun at him. They stood looking at each other, in a showdown, for almost a minute. Then she shot him right between the eyes. My dad walked around with a BB above the bridge of his nose until some lady noticed it and squeezed it out a week or so later.

This was around the time my dad had taken to playing with matches and lit the couch on fire. Peggy hid him in the wardrobe closet when the fire department came over, and they both got beaten for it—“whooped,” as they call it, or a “good whoopin’”—which they laughed about as adults. Peggy and Dad were close and would discover much of Shreveport together, walking through the sewers in the neighborhood and then popping up and out of the manholes. They’d look around and guess the neighborhood, and then look up at the street signs, which they were barely old enough to read.

They also played a game at Granny’s vanity mirror, where they’d place the other in a chair as one would stand behind. They’d stare at each other in the mirror, and the person standing would hold their hands just inches away from the other’s face. Then the standing person would swing their arms wide as if to slap the other’s face, and freeze their hands while having their stare-down. When they finally did slap, it was the other’s turn to go. They’d play for hours and the game always ended in tears. But they’d make up, because they loved each other. And that was the fun of the game.

* * *

–

In the sunroom, Granny had an embroidery hoop mounted on an adjustable tripod that I’d sit at for hours. I’d look at her pattern book and copy the stitches onto the fabric. I liked the backstitch—the needle moved forward a few centimeters, then went under the fabric, pointing through and creating a gap to be filled—then traveled backward again to pull the thread forward, returning to the exact point where the previous stitch ended. With the stem stitch, you wouldn’t see that gap because the needle threaded just barely a centimeter, under the overlap of the previous thread. The split stitch took the needle through two strands (if you doubled your thread) and could backstitch along to create branches. Granny sewed a map of the United States that included every state flower. It was made from a pattern, but still. Like Ophelia, she would say, “Pansies are for thought,” and she liked to paint them, too.

* * *

–

My grandfather was named Youree Posey and we called him Paw Paw. He was born in an old railcar to David Posey and Ethel Maybell Gage, who went by Maybell. The Gage side of the family was Irish and David’s father was too, but the Maybell Gage side was of Cherokee descent from the Trail of Tears. She was several feet taller than her husband and “towered over him,” according to Paw Paw. These were such tough times with the Depression and, before that, the cowboys and Indians. I liked picturing her towering.

Paw Paw’s dad was especially tough. One time, he put a knife in the fire to sterilize it so he could cut his own tonsils out. He followed through with it, too. He also shot and killed a man who trespassed on his property, which you didn’t do back then, as it was against the law—both things. When he went to court he showed no remorse whatsoever. When the judge said that he was free to go, David volunteered even more information than needed and shouted, “I’d do it again and shoot him even more times, if anyone ever went on my property!” The judge banged the gavel—“Quiet in the court, quiet in the court!”—and my great-grandfather marched out of there, high on the waves of drama.

Maybell died when Paw Paw was thirteen. Back then, if you didn’t have money for a hearse, the casket was put under a school bus and that’s how my great-grandmother traveled to her grave. David got drunk and married another woman shortly after, but when he sobered up the next day, he ran her off. He married again, to someone named Miss Ruth, but that’s all I know. I don’t think she was a lot of fun or particularly nice. Not long after, when Paw Paw was fifteen and riding his horse in the country in Arkansas, he picked up an African-American boy, who was around six or seven, and called him Smokey. Smokey called Paw Paw “Yick,” or “Mr. Yick.”

David, for some reason, said it was okay if Smokey stayed, as long as he ate off of Paw Paw’s plate and not his, and everyone in town came to know my granddad as the teenager who rode on his horse with Smokey at his side. Paw Paw even rubbed Smokey’s head for good luck when he played cards. Both Paw Paw and Smokey were “dirt poor,” but they were friends and loved each other.

Paw Paw was a great athlete and played basketball for the semipro league. This was in high school and it was a self-made team. He stayed in high school an extra year to play on the team so he could make money. He even had a German pseudonym, Youree Hans, in case there was press at the game. This way he wouldn’t have to speak or cop to being overage and still in high school.

Paw Paw left his family when my dad was fourteen, and my dad was made “man of the house.” He had to “grow up fast” and Granny “took to bed,” to use my father’s words. Granny even made him get her “feminine products,” which embarrassed him. She bad-mouthed Paw Paw, because she was heartbroken, and she manipulated her kids with “call your father and tell him that you miss him.”

* * *

–

North Louisiana had a pocket of Catholics, which was unusual in a Protestant “Bible-thumpin’” Southern town. The DeLatin side of the family were deep Catholics: Granny’s aunt was mother superior at Saint Vincent’s Convent School (Eulalie DeLatin was her name) and we had another relative in the 1800s who was a big Catholic, Monsignor John Van Degar. The names sound like soap opera stars, don’t they? My dad loved the Jesuit school he attended; he loved that it was smart and strict and that he learned Latin. He

was a star student and he found father figures in the priests there, and thank God, there was no weirdness. Aunt Peggy loved going to boarding school at Saint Vincent’s and the nuns were fantastic and lovely. She watched them outside the schoolroom’s window as they rode mules pulling the plow to grow vegetables and crops to feed the chickens and cows. Then they sold it all to Sears in the mid-sixties and she was rightfully pissed off.

When things got too heavy at Granny’s, I’d sit in front of the gas-fire radiator and stare into it, then run to the bathroom to look in the mirror to see if the tips of my lashes had turned into ash. Granny didn’t have separate soap with flowers on it like Nonnie did—there was just one bar, the unnatural pink of calamine lotion, which didn’t lather much. She had rippled candy in Depression-era glass bowls, which were beautiful, and she had just a few demitasse cups, which she loved to show me. She’d sit in her rocker in the living room and sing the depressing cowboy songs of her childhood, like “When the Work’s All Done This Fall,” which she sang to her own children and made them cry so hard they’d hug each other. This particular song was a real guilt-ridden heartbreaker, about a cowboy who got stampeded by his own cattle and died, right before he was about to get all his work done and make it home to his heartbroken mother—who told him not to go in the first place. Don’t leave your mama, boys.

Paw Paw would come over for Christmas to receive the bad vibes from Granny and the kids. Paw Paw was at the Office a lot—which was the name of the bar that he owned. He married a woman named Kathleen, who he loved very much but died, and then he had a lady friend named Helen, who had a pouf of light blue hair—a touch of magic, I thought.

When I visited Helen’s house, which was tiki chic seventies style, she served us mixed nuts in bamboo bowls and had needlepointed cozies over Kleenex boxes. Everything was mostly brown and I dug the brown shag carpet and rattan furniture. One time, she put her hands on a table and repeatedly said, “Come up, table. Table, come up.” She said this repeatedly and for too long, in the hopes that her magical powers would reveal themselves to us. They didn’t, unfortunately. I really wish they had. I would’ve liked to have seen that. The gold lamé genie slippers, with the slightly curled pointed toes, reminded me of Aladdin, and with Helen’s blue hair it wasn’t a far stretch to picture a table floating up like a magic carpet.

My granny and my aunt Toni-Anne were much more grounded. They’d eat on TV trays in the bedroom and watch “the stories.” When I was on As the World Turns, it made them very proud. “You got my widow’s peak,” Granny would say, before talking about how handsome Holden was. Holden was the hunk on the show, played by Jon Hensley. “He’s really nice, too, Granny,” I’d say. “You’d like him.” I told her how, on my first day of work, the woman who played my aunt Barbara said, “Be careful who you share your secrets with because these walls have ears.” Colleen Zenk turned on the waterworks like nothing I’ve seen in my life. Granny loved that dish. As the World Turns was one of the earliest soaps—its first airing was shot live in 1956. She loved Eileen Fulton, who played Lisa Grimaldi, and Helen Wagner, who played Nancy Hughes, both of whom were there in the beginning. I’d tell her how classy and nice they both were in real life, since they’d kept her company as she took to bed and martyred herself in her forty years of heartbreak. I told her how nice the producer of the show, Laurie Caso, was when he asked if I’d like to get out of my contract early because they needed to put Holden in a coma before Labor Day (his love story with Lily was huge and they needed to focus on that). I told her how Laurie hugged me like a dad and was so sweet that I cried. She loved all that.

I didn’t spend as much time as I would’ve liked at Granny’s house, though. During one visit, when I was only around seven, one of my cousins got me to put an “f” in place of the “d” for “duck,” and I walked up the steps of the porch and said the F-word to all the grown-ups. That pretty much ended my solo time at Granny’s.

When Granny was dying, she called Paw Paw on the phone. “Does my baby girl want me to ride in the ambulance to the hospital with her?” he asked her. He rode with her and held her hand and was able to pay for the funeral. When he died, he left all his kids money and my dad his prized coin collection. One of his neighbors wrote a piece in the paper about how kind he was to his neighbors. All he wanted to live for was to be remembered as “having a good name.”

For the DeLatins and the Poseys, this apple pie recipe. It’s really easy.

Skillet Apple Pie

1 stick of butter

2 pie crusts from the grocery store

Big Ziploc bag full of sliced apples

1 cup packed light brown sugar

1 teaspoon cinnamon

Preheat oven to 350º. Melt the stick of butter in a cast-iron skillet, then add one of your pie crusts. Fill the Ziploc bag of apples with sugar and cinnamon and shake. Pour the apple-sugar-cinnamon mixture onto the pie crust. Cover the apples with the other pie crust upside down, as a lid for the apples.

Put it in the oven and watch the butter bubble and cook the edges of the pie. I think this takes about 45 minutes. May God bless America.

6

Indie Days

I can always tell the Party Girl fans because they look fun and some even tell me that they wanted to live in New York after they saw the movie when they were kids. When we made the movie, we talked about giving the kids something to dance to while they watched it on TV.

When I was doing press for Party Girl, I met a journalist from India who was so excited because it reminded her of Bollywood cinema, and I’d never seen a Bollywood film. She explained that characters in Bollywood films break out into song and dance all the time and that these breaks are shot like music videos within the film. Sometimes the breaks are fantasy numbers, or party scenes, or declarations of love or heartbreak. There’s an air of performance to it all, which is why she thought I’d be a fan. And now I am. Sholay is the film I’d recommend seeing first. It’s a classic.

Daisy von Scherler Mayer directed Party Girl, which she cowrote with her friend Harry Birckmayer. I’ve gotten few parts that I auditioned for and that was one of them. Auditioning feels like my real self has been punished and sent to my room, while my pretend self is forced to make nice when there is nothing that I’ve done wrong. At an audition in my twenties I spazzed out so much that the casting director asked my agent if I was on drugs. I wasn’t, but just had lots of energy and was excited to be there. I was going out dancing with my friends a lot, though, so with Party Girl, I was cast in a role I’d been living.

I remember passing Sam Rockwell in a basement apartment in the East Village, where the auditions were held. We had met at a reading together, at a theater somewhere in midtown, a year or so before. I’ve always loved his vibe, it hits close to home—cowboy rodeo meets Chuck Barris from The Gong Show. He later played Barris in that movie Confessions of a Dangerous Mind and learned to lasso for Sam Shepard’s play Fool for Love, a part he’d always dreamed of playing. I forget the name of that part. On closing night, I joined him and his friends backstage for a toast of whiskey, which I drank with added drops of oregano oil to fight a flu I’d felt coming on. Later they went out and Sam was still holding on to his role by lassoing people on the sidewalks.

We’d worked together in a 1995 film called Drunks, which was shot in a church in Harlem. It took place at an AA meeting, led by Richard Lewis’s character, where everyone shared their stories of getting sober. The actors’ “holding area” was in a room off the large congregation room, with individual dressing rooms separated by bedsheets. Inside these “rooms,” which were about four feet in diameter, sat a metal chair draped with our character’s clothes. I remember actors prepping their monologues in these rooms, which struck me as holy confessional booths, minus the priest. We’d all tiptoe around to respect each other’s privacy because some of the older actors were sleeping.

There were maybe a hundred of us, total,

all held in this church, so there was nowhere to go except outside, and it was cold. We drank lots of coffee and I smoked outside with Kevin Corrigan and Sam. Kevin has a similar essence to Christopher Walken—idiosyncratic and human. And Gary Lennon, who wrote the play the movie was based on, was receptive and cool and always around; he went on to write for Orange Is the New Black and won some Emmys. Pre–Ally McBeal days, Calista Flockhart was there and fully committed to her work. There was Dianne Wiest, who was luminous and truthful and beautiful, and Amanda Plummer, wholly authentically sensitive, and LisaGay Hamilton, who was just completely fierce.

I was a big fan of Spalding Gray, the monologuist, who performed his own monologue in the film. He’d stand poised and silent, sometimes by the doorway between the two rooms but mainly, almost always, close to the wall, like an insect. He’d glide around, peering over people’s heads as if they were antennas for his own intelligence or creativity. Looking through us or above us, in his vacuum-land. He was never without his yellow legal pads and no. 2 pencils, which he held to his chest while walking and on his lap when sitting. I remember telling him that I was a fan, and he showed me his pencils and told me how he always wrote in longhand. That was the extent of our only conversation.

Faye Dunaway swept in for a few days for a monologue, and she had a birthday during the shoot. Everyone came out of hiding or solitude to sing to her in the back of the church. Before she blew out her candles, she said, “What should I wish for?” Her hands were held up, splayed in a court jester gesture, as if to say, “You tell me, fellas!” And with really good timing she said, “That I remember my lines!” and blew out her candles as we all clapped. She was touching the shoulder of a first AD named Burt or Burke, who she had worked with twenty-five years before. It was a long time ago, so I don’t remember. I recall he wore a kerchief bandanna around his neck, like a wrangler rustling cattle. Faye Don’tRunaway.

You're on an Airplane

You're on an Airplane