- Home

- Parker Posey

You're on an Airplane Page 2

You're on an Airplane Read online

Page 2

I did a little indie movie with Demi Moore and vividly remember her saying, “Sometimes you gotta pay the devil.” She was walking backward and shrugging with swagger, like a star in a Western film, her hotel keycard in her hand, ready to open the door. We played Celebrity at her house that year, with other celebrities like Ashton Kutcher and Bruce Willis. I didn’t play because I don’t like games but I love watching people play them.

After that breakdown, I called my reps asking if they could look into pitching me as a weather girl on the Today show. They thought that was funny but I thought it was a good idea. Weather is something you can count on—whether the weather’s inside or whether the weather is outside. The turban suits you.

2

How I Got My Name

I was born fighting for my life. That’s how the story begins, or the one my parents tell me, which they perform really well, too. I stopped breathing at a certain point, and my dad, who was kneeling outside the ICU window, said, “Please, God, let my baby girl live, please, please, please . . .” He had a six-pack of Budweiser beside him, and as he drank the beer, it occurred to him: “My daughter is the size of this beer can. She is a beer can on legs.” When he tells it he mimes holding a beer can, and mimics my legs sticking out of it, and we laugh. He was in his army gear in the hospital—he was stationed in Baltimore—and he put down the can and returned to his intense praying. “Please, please, please, Lord,” he said, his hands clasped. “Let my little baby girl live!”

I then let out a scream, as if on cue.

The story, told to me my whole life, at every birthday, helped me imagine that my dad could get God on the phone whenever he wanted, that if my dad prayed hard enough, God would pick up his very important telephone and take Dad’s call. Since I grew up Catholic, I imagined the saints and angels as holy secretaries, clambering to get to God, specifically for my dad, despite all the other work they had to do. There was Saint Christopher, who carried Jesus as a baby, without knowing who he was yet, and was made the patron saint of travel because he was just nice. He had to help everyone traveling, yet he could answer my dad’s call to God the very moment I was born. There was Saint Anthony, helping people find their lost keys, and he, too, would drop his responsibilities in order to get the phone to God, because I was being born and my dad had persuasive powers.

* * *

–

My mom had gone in for a checkup at the hospital on Halloween. The story goes that the doctor felt around in her uterus and “shook his head in disbelief.” Then he went to get the nurse, who came in and felt around, and she and the doctor started laughing. My mother, in the stirrups, was left out of the joke. Then the doctor told her she was having twins, which was a real trick-or-treat moment. I was born a week later on November 8, 1968, at 3:33 a.m., despite a due date of January 7, 1969. My mom was just twenty-two, a baby herself, and describes this time as being “completely overwhelming.” I can imagine.

Excuse me, can I have a Diet Coke? Thank you.

My twin brother, Chris, was closer to the door on the way out. Hanging out in utero together would be the closest we’d be in our lives, and the act of being born was, of course, our first trauma. I’d later learn that my mother had been in utero with a twin, too, but that she’d lost her brother. My brother was first and jaundiced, weighing five pounds. I came out three minutes later. We were both breech and pulled out by our feet, and my mom was fully sober for all this. Can you imagine? She says, “I swear, I felt you come out from under my arm!” Maybe next year for Halloween I’ll make a big hat that looks like an arm and just come as myself. No, I think a can of Budweiser would be too obvious.

One of my first memories—whether or not it’s “real”—is of my brother being wheeled away from me on a gurney. The image is black around the edges and blurry, and I’m not sure if I created this moving shot or if it happened. After he was taken away, the doctor came into my mother’s room and said, “Your little boy is fine, but your girl, we need a name. For the death certificate.” Hearing this story as a child made me feel as if I’d already “made it,” having gotten through being born—it was like applause.

So, my name: When my mom was eleven, she was a Girl Scout, and her friend’s older sister had a daughter named Parker. Back then my mom thought to herself, “If I ever have a little girl I will give her a strong name like Parker.” Her own name was Lynda, spelled with a “Y,” and she always hated it. “The obligatory Y,” my mom called it. Why, Y, why? So when the doctor asked for a name, my mom said Parker for my first name and Christian for my middle name, because they wanted the help of Jesus and of the Trinity: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Posey was from my father, obviously. My mother says she thought the name Posey was silly, and it really is. I know, my name sounds made-up. I will most definitely make that arm hat for Halloween next year and come as myself.

I was just two and a half pounds and spent six weeks in intensive care, and the nurses’ hands, enclosed in rubber gloves, held me inside the incubator. The first photograph I have of myself is of the moment I was brought home from the hospital. I’m in my mother’s lap, wearing fake eyelashes. When I asked my mom why she put fake eyelashes on me, she said, “You were so small, I didn’t know what to do with you.” She also said, “You were born a nervous wreck.” She’d seen me in the hospital being fed by an eyedropper, like they do with baby birds, and I must’ve looked unreal to her. I look at home with these eyelashes, though, huh?

* * *

–

Later on, in my twenties, after a stint of playing too many roles in too short a time, the birth and death of those characters triggered my birth trauma. I crawled on the floor to my psychoanalyst, Mildred Newman, and sat at her feet and cried the trauma through me.

Nora Ephron was a former patient of Mildred’s and described her as a white witch, but to me she resembled my granny, in an old-world European way. Mildred helped me through a lot, especially when I became more known and tried to isolate myself from my success, as if it were a catastrophe. Being famous is a birth into something else and some people can handle it better than others.

The diagnosis was simple to Mildred: if my good wishes came true, then my bad wishes could come true as well. My psyche was frozen in that battle. At her feet, I was in a trance, and she said, “Those nurses held you and looked at you with love and care . . . through a glass box. Now look at what you do.” I felt her spell and my ice started to crack.

* * *

–

When Dad left the army base in Baltimore for Vietnam, Mom drove us down south to Shreveport, Louisiana, in her red convertible Fiat. It was still winter but we were kept warm on the floor in the backseat, close to the engine, where the humming vibrations soothed us, and where I developed a preternatural sense of smell for gasoline, which I’ve always loved.

We’d stay with my grandparents, Nonnie (whose real name was Faye) and Glenn Patton, in their ranch-style house on Lovers Lane, where tensions were rife and fraught but disguised and kept separate in that Southern way—left behind closed doors and swept under the rug. My parents had eloped for a shotgun wedding and had no real home together quite yet, and Dad got drafted in a war that hippies were protesting and most people, including my mom, were questioning. To this day, she still says, “Why were we over there?” like a wife and mother. She became a student teacher in Monroe, Louisiana, and taught junior high. She lived in an apartment and made friends with her neighbors Pat and Duddy Garret.

This lasted for three years, with us back and forth to Baltimore, when Dad had breaks from the war. He was a captain liaison officer. Chris and I said “Dada” for the first time into a reel-to-reel tape recorder that my mom mailed him. We’d listen to his voice and she would point to the tape recorder, saying, “That’s Dada.” Once, when he came back for a quick trip to the base in Baltimore, my dad saw us “screaming bloody murder” and holding tight to our mother’s legs. He called ba

ck to the stewardess at the top of the stairs and said, “I’d have an easier duty back in ’Nam!” We didn’t recognize him because he wasn’t a tape recorder, and the noise of the plane was fierce in our ears, but when he got close to us on the tarmac, my mom pointed and said “Dada” and then we started the “Dada” bit, which had become a song at this point, and Dad sang along and swept us up, carrying us to the car.

Nonnie knew a neighborhood girl named Missy, who was six years old and blond with pigtails and whose mother was a flight attendant. One day, Missy was walking alone in the neighborhood and knocked on Nonnie’s door, asking for candy. Nonnie loved the gall of this girl but told her, “You’d better ask your mother if it’s alright. It’s not safe to knock on the doors of people’s houses you don’t know, so go on and ask your mom if it’s alright and then I’ll give you some candy.” The girl went away, and Nonnie watched through her kitchen window as Missy stood at the end of the driveway for several minutes, alone and tapping her feet and swaying to pass the time. Then she watched as she walked back up the driveway and knocked on the door again. When Nonnie opened the door the second time, Missy said that her mom said it was okay to have candy. She had some nerve and was a good little actress.

Nonnie loved this story so much that she called me Missy, in tribute. But I felt something was amiss in my not being older and blonder, in not having hair long enough for pigtails. So I’d daydream about being someone else. When I was nine, I told Nonnie that I was going to be a movie star and she told me that she was going to be the president of the United States—guess I won.

3

Why Are You an Actor?

I’m an actor because funny things happen to me and shame flirts with me. I left my apartment once and I didn’t tie my harem pants tight enough around the waist, so they dropped to my ankles while I was walking down Fifth Avenue. I found a stranger to help my shame and wanted to share a laugh. This lady was an older woman in her eighties with great style—big glasses, sharp quilted blazer—and I smiled, and turned my inner camera on so I could remove myself from the situation. I said, “My pants fell down,” almost like “Hi, how’s it going?” She didn’t respond or laugh because she wasn’t an audience member in my show. She grimaced, maybe thinking I was a streaker, and walked quickly past. So I said it again, to absolutely no one, but to the air around me and to the buildings, as I pulled my pants back up and tied them back together.

When I’m asked, “What’s it like being an actress?” I always say, “It’s like walking around with your pants down and around your ankles.” It’s somewhat of a stock answer so I was happy to experience it for real. Embarrassing and shamefully uncanny things that are at first humiliating and only funny later seem to naturally happen to me. I think this is a big part of why someone becomes an actor.

* * *

–

In my Chelsea days, in the nineties, I’d start baths and forget about them, flooding the beauty shop downstairs. But Kathleen, the owner, was laid-back and cool. “It’s the third time in a month I’ve flooded the beauty shop downstairs! I forgot about it! How could this happen again?!” Like forgetting is something that happens to you and not something that you participate in or that you’re like, you know, responsible for creating.

You’re stressed out and your friend calls and says, “What are you up to?” and you say, “I’m looking for my phone!” You look for your glasses for ten minutes while they’re on your head, or you’re wearing them. I’ve slipped on banana peels several times in my life, and not as a joke. The door has opened when I’m in the bathroom many times because I haven’t locked it, and the other person is more embarrassed about it than I am.

I’ll never understand how I could watch my hand casually toss my Nokia nugget into the gutter and into a puddle as I strode down the sidewalk. It felt like something out of The Matrix. This was made more absurd and uncanny in that it was the first of three times that I “lost” my phone that week. The second of those times, “losing” it just meant leaving my phone somewhere because I didn’t want to be reached.

But the third time, I was at Madison Square Garden with my eight-year-old niece, Isabella, for the Cirque du Soleil Christmas show. Have you been to the theater there? It’s huge, just . . . Wow. It holds around 5,000 people. Our seats were close to the stage, down in E or F of the first level, right in the center front.

We arrived at the perfect time for the theater, with less than ten minutes to wait—enough time to get some water, enough time to maintain our excitement and focus for the magical show, and enough time for me to wink at those who recognized me and wait for the curtain to rise. It was then I realized that my phone was missing. It felt like some bad joke. “Bella, where’s my phone?” I asked. She said, “Didn’t you just buy one on the way up here?” I had indeed, in Chelsea, when I hopped in a cab to swing by to get her.

So we’re digging through my bag and looking under the seats, and the people in front of us and behind us are looking as well. I’m patting my pockets and shaking our coats. “This is the third time I’ve lost my phone this week,” I share with the strangers around me. They’re laughing, of course. Bella says I must’ve placed it on the bar when we got our water. I ask the kind strangers if they could watch my niece for a second and I scamper, all hunched and hiding as I run to one of the theater ushers. She points me to the security guard, down and up front, standing at the lip of the stage. “I’ve lost my phone,” I tell the security guard, exasperated.

The guard points me toward the lobby, up the long flight of stairs. Should I stay or should I go? It was daunting. I would have to run.

The lights are dimming on and off, the intro music has started, and I am out of the gate—hauling up those stairs, two at a time. Panting, I ask the bartender if I left my phone there and he says no, but I can check the office at intermission. “Okay! Good plan,” I blurt out, and start my hunched and speedy jaunt again, down the steps, where the lights have dimmed but the theater is not yet completely dark.

There’s a spotlight on the performer playing a burglar elf, dressed in green spandex. He’s dancing around, introducing the show in Cirque du Soleil fashion—animated like a court jester. He warns the audience of a pickpocket and instructs everyone to hold on to their purses and wallets. I’m breathless and shaking my head like a crazy lady as the spotlight catches me mid-gate and I freeze: 5,000 people laughing. The joke’s on me as I run back up the steps to a security guard holding my phone out to me. Caught.

Things like that, that just “happen,” are the reason I’m an actor. David Harbour, who plays the cop in Stranger Things? I ran into him a couple of years ago walking with a crutch, in a full-leg cast. I was eating my pretzel croissant from City Bakery and he was going inside for a cookie. I asked what happened and he told me he had to back out of a production of Troilus and Cressida at Shakespeare in the Park, where he was to play Achilles, because he tore his Achilles heel. Sometimes you’re in the play, but not the play you’d intended—and that’s what’s strange with a career in acting.

* * *

–

My mom was always burning herself in the oven; she said it was hereditary and that her father was always burning himself on the oven, too. “Is Glenn going to have a Band-Aid on?” we’d ask on the way to visit my grandparents, and when he did, we’d all laugh. In the house were lots of Band-Aids, peroxide, Neosporin, and, back then, Mercurochrome and Merthiolate, which we called “monkey blood” because it stained red. You’d blow on it if it was Merthiolate because it burned like hell and you’d beg Mom to use Mercurochrome because it didn’t burn. All of us over the age of thirty have mercury in our blood—they later learned it was poisonous to the brain, which is too bad because the stuff worked.

Needles and thread at the ready for mending, and baking soda for stains. I liked the grunge period in the nineties when Gen Xers wore ripped clothes with safety pins and tied flannel shirts at the waist—shirts that l

ooked like hand-me-downs from your older brother, with missing buttons left unmended.

When I was a little girl, I had a rag doll that got so dirty and worn from all my playing that she’d get thrown in the washer and dryer repeatedly. She was 100 percent cotton. When her blue felt eyes came off, my mom sewed new ones back on with black thread, making her eyes solid pupils. I called her Muffin—there’s a nod to her in my Waiting for Guffman monologue, in the deleted scenes—and she had yellow yarn hair that was in a permanent up-swirl from my hand holding tightly on to her head.

I have a series of photos of Muffin and me, with my mom and dad and brother, from when we were five. We look picture-perfect, although the day had started badly, with me running away from the camera lens. I liked to say back then, “Don’t look at me! Don’t touch me!” when someone wanted to take my picture. I’d even splay my hand in front of my face and grunt as I said it. It was primal for me, but for others, it was funny. I know, look at me now.

The photographer didn’t scare me, but the camera did. I think it had something to do with how my parents changed when the camera pointed at them, and that I didn’t know my part in the scene. But also, I loved Muffin and wasn’t sure that my parents would want her in the picture because she had weird hair and looked poor and dirty. But the photographer liked her, so eventually he led me and Muffin to a flower bush to smell the flowers. My mood shifted as I found myself in the scene everyone wanted me to be in, and I was comfortable in the frame of the shot.

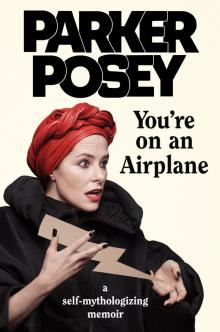

You're on an Airplane

You're on an Airplane