- Home

- Parker Posey

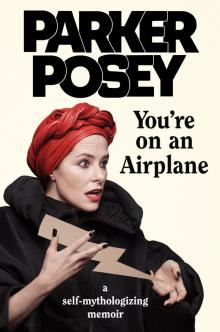

You're on an Airplane Page 11

You're on an Airplane Read online

Page 11

I called my agent Brian right away and told him he had to sign this guy, that he was going to be huge star, but he didn’t listen. I see Brian every few years and mention McConaughey so we can share a rueful moment.

Wrapping Dazed was bittersweet and the experience gave me the meaning of the word. It was the high school we felt we belonged in. When we weren’t working we watched the other actors and everyone was just so good. I’m thinking now of Adam Goldberg and Nicky Katt during their fight scene, the shot of Jason London looking around when he was on the football field at the end and the music that made it all what it was. Rick called the music another character in the movie but it was the soul.

* * *

–

In 2003, there was a ten-year reunion for Dazed in Austin, and around twenty of us from the cast were there. It was a trip, and a few thousand people showed up. Joey hit the mic with “Fry like bacon” and I shouted out “Air raid!” McConaughey breezed onstage and everyone flipped out. The screening was in a park and people brought blankets to sit on and partied with the movie; some even stood up to dance when a song came on.

We all sat clumped together on the grass and there was one scene, of Mike and Tony and Cynthia getting out of their car, that had a boom mic in the reflection of the windshield. I looked over at Rick, who noticed it as well, and ran over to him. He was laughing and said, “I made a drive-in movie!” like it had just occurred to him. The extreme close-up of the keg was especially funny, as people got on their feet to cheer at it.

* * *

–

Rick was in New York in early 2016 for his “spiritual sequel” to Dazed, called Everybody Wants Some!! I was invited to the premiere by the publicists, and they put me down as one of the hosts. I walked the twenty minutes it took to get there, in the fast stride that the early spring gives you. I caught up with Rick for a few minutes and said hi to Ethan Hawke, who was there to introduce the movie. After posing for some pictures, Ethan said, “You should come onstage with me,” and I said something like, “I would start talking and then say too much.”

I walked over to the after-party, which was in a small Mexican restaurant on the Lower East Side, with David Cross joining me, who’s always been too cool for school. I met Maria Semple almost immediately when I got there. Rick’s new movie, Where’d You Go, Bernadette, is based on her book. My agent had been “pursuing the project,” “chasing it,” “tracking it.” Making sure I was “on everyone’s radar.” I ordered a drink and was eating the chicken quesadilla and nachos that were sitting on the bar. She asked me what I was working on, and I said, “Other career options, new media ideas, new forms, courage, a positive attitude, gratitude.” I told her I loved her script, and how rare it was to read something where the characters feel like you and your friends. She was super nice and said I was on the list of actresses to play the nemesis of Bernadette. I was more right for the lead, I told her, but knew how the system worked. She mingled away after that, which was a defeat to my bad attempts at mingling. You can’t be direct while mingling because that’s not what mingling is and I’ve never been good at it.

I got pulled over by the publicist to take a photograph with Rick in front of a mural of McConaughey, airbrushed onto a brick wall. He was leaning against his car, as Wooderson, and Rick and I leaned against the wall to join him there. After the shots, Rick asked what I was working on, which is the same as “How are you?” in showbiz-speak. I said, “Other career options, gratitude, courage . . .” I felt like crying, for so many different reasons, and sensed he caught a tinge of the particular pain that comes with love or nostalgia. He has nice, kind eyes. “Aw, Parkey,” he said. “I hope we get to work together again.”

During my walk home, I found “Sweet Emotion” on my iPhone and wished I still had my Rollerblades. There’s no better intro to a song. Where did those Rollerblades go? Did they leave without me?

We’re cruising at the right altitude to take our seat belts off.

14

Southern Gothic

When I was a baby, I’d calm myself down by rocking back and forth on my stomach for several minutes at a time. Years later, I’d take a kundalini class and do that same thing but for ten minutes; it’s called Bow Pose, and it keeps your energy flowing. Kundalini yoga is the one where they wear all white and sport turbans and get high on breathing. They reach this blissed-out state by doing lots of “breath of fire”—where you hold one nostril closed with your ring finger and breathe four times (focusing on the out breath) and then do the other nostril—pushing your belly in sharp, like a punch, and forcing your breath out to the count of four. It’s like alternating leg lifts with each of your nostrils and it’s not pretty. But rocking through Bow Pose as a baby helped me process what I’d been through, what with being born and all. Looking back at that time, it was preparation for when I’d be able to stand up to deliver my first performance. I’d work myself up so much, crying and shaking, that I’d stiffen my body and clench my fists at my side, like rigor mortis. These fits were simply entitled “rigors” by my parents, and when company came over, I’d perform them. It was up to me how long they lasted, but everyone knew that when I’d bite my own arm that the show was over. And then there would be applause. So, that’s when I started performing, age two going on three. It’s sad to think it was some of my best work.

The whole family would join in on the show: Paw Paw would take his teeth out (which brought the house down), and Nonnie, over at Lovers Lane, would get on the floor and do one of her tricks, like hike up her pencil skirt and pull her leg up to wrap her ankle around her head. She didn’t know this show-stopping trick was the yoga pose called Eka Pada Sirsasana. If you have trouble pronouncing words that sound like a sneeze, you can call it Foot-Behind-the-Head Pose. I can do this one, too. Did you know that “yoga” is Sanskrit for “look what I can do”? That’s my friend Jason’s joke.

Glenn, my grandfather, taught me how to whistle with my fingers—it’s good for hailing a cab and I think of him when I do. Nonnie could spit through her saliva glands. I don’t know how she did this. I’ve tried and am bummed that I didn’t get this gene, but she’d stick her tongue to the roof of her mouth and then a muscle would somehow activate and spit would fly out, like a spray from a water gun. We begged her to do this trick all the time, but she wouldn’t often oblige, because it wasn’t very ladylike. When she did, she’d excuse herself afterward, as we applauded and screamed. She’d come back into the living room while we were still clapping, like any professional actor returning for an encore. We called my uncle Jimmy “Uncle Eyeballs” because he could flip the tops of his eyelids up, and keep them there, and still look at us. He’d also get his teeth cleaned by asking one of Nonnie’s Yorkies to clean them: “Benji! Teddy! Lick my teeth!” And they would stick their tongues in his mouth for a full-on session. He was also very gifted at making fart noises under his armpits—various kinds of noises. My brother inherited this gene, and when he does it, he’ll call out things like “French horn” or “question mark” or “silent but deadly.” When Hee Haw came on the television, the entire family knew we could upstage anyone on that show, were we ever called upon to do so. It was a tough house and we felt good, watching it all together, because we knew that we had better material.

* * *

–

My dad says that as a child I reminded him of Stan Laurel of Laurel and Hardy. He refers to a time when my brother and I were in the bathtub and he heard a scream. When he came in, Chris had a bite mark in the middle of his back. When Dad asked if I’d bitten him, I said no and stared deadpan at him, like Stan Laurel. I almost got to be in a movie about Laurel and Hardy as wife to John C. Reilly’s Oliver Hardy. John and I met on The Anniversary Party and he knows all the words to Jesus Christ Superstar, as do I, so we rocked out in my room at the Chateau Marmont—“Must die, must die, this Jesus must, Jesus must, Jesus must die!” I love that guy and would have loved to ha

ve played his wife on-screen, but I got Lost in Space and wasn’t available.

When I was four, I left the bathtub, completely naked, to knock on the neighbor’s door for a visit. I loved hanging around old people’s homes and perching myself on their armchairs or sitting on their kitchen counters. That was my vibe. There was a single lady who lived next door and was pretty, with long dark hair and a tiny poodle named JoJo. When JoJo was sick, my neighbor would crunch up a white pill and put it in the center of an Oreo cookie to feed him. I thought that was cool, being a single woman with a poodle. I’ve had Gracie for fourteen years and as much as she would love an Oreo cookie, she doesn’t get one. I’ll give her the occasional Tic Tac though—mint. She likes mint.

My first time on a real stage came when I was almost eight, at a camp called Strong River in Mississippi. The counselors picked me to come up with a show, or “presentation,” really. I made up something about Little Red Riding Hood uncovering the case of Goldilocks and the Three Bears. Telly Savalas from the show Kojak was my muse, and I walked onstage with a red tablecloth wrapped around my head and a Tootsie Pop, saying, “Who loves ya, baby?” That was Kojak’s trademark, and when everyone laughed I remember thinking, “This isn’t funny. I am a detective.” I maintained character and waited a few beats for the laughter to die down and then went on with my next line.

I’d take the stage seriously when I was nine and started ballet. It was expensive and I was glad my dad could swing it. I couldn’t tap-dance on our wooden floors but there was some tile in front of the fireplace on which I could “shuffle off to Buffalo” or “shuffle, ball change.” It could be annoying for my parents so it was best to wait until I was alone. I couldn’t be bothered to count in order to learn the routine for the recital, so I was sure to be close to the wings to shuffle-ball-change my way offstage. I only really cared about the tumble routine to the Star Wars theme that year, anyway. The following year, my teacher Ms. Linda and her assistant held auditions for chorus dancers in the company’s production of Coppélia. Ms. Linda was both elegant and strict, and when I auditioned, I looked directly at them, which made them laugh. She said, “The audience is in the mirror, behind us. You can’t look directly at us!”

My mom was there, too, standing to the side of the room when Ms. Linda told her I had charisma, and when I asked what that was, Ms. Linda said it was talent. I was relieved to be called something that was good since I was a devoted daydreamer and adults often interpreted this as meaning I was developmentally challenged. My parents had had some doctor come over to look at my brother and me when we were two, who said we were going to be “retarded” and to hold us back a year in school. My parents laughed their heads off when they repeated this, because the doctor was quite the character and they thought he was out of his mind. I don’t remember him at all, but my “rigors” made them wonder. Everyone knew I came out half-baked or undercooked and should’ve stayed in longer, so maybe there was something wrong with me. But everyone enjoyed the rigors and I enjoyed performing them, so there you have it. That doctor was a dork.

I spaced out in grammar school, so much so that my dad went so far as to attach jingle bells to my notepad so I wouldn’t forget to write down my homework. This embarrassed me, but so had my red cloth shoes at kindergarten graduation, which stood out from the suggested, but not mandatory, expensive white patent leather shoes that all the other girls were wearing. The red shoes were cuter because they had flowers on them, and since they were cloth, I could wear them again. My mother could make things beautiful.

The night before first grade, I slept in my uniform. Up until that point, I’d just worn my own clothes to school and was excited to wear the jumper, like it was a costume. In second grade, I wanted to lie on the vision test so I could get some eyeglasses, as a prop. My parents started to think I might have a learning disability so they got me tested at the college in Monroe. I colored with the ladies who ran the program, who said I was creative and there was nothing wrong with me.

Ms. Linda accepted me into the ballet company, which meant I could go on pointe by age eleven. I danced Coppélia for the recital, putting on my own makeup and false eyelashes like Nonnie did, and like my mother did to me on that first day home from the hospital, on the army base in Baltimore. I made the local paper at age eleven when a Turkish man named Tanju Tuzer came to teach a three-week class. He was gorgeous and graceful and had body odor, which made him stand out even more, in my mind, as someone “serious.” We made the paper together. In the picture, I’m pointing in tendu, and Tanju Tuzer is holding my hand, and the girls in the background look intense and focused and maybe jealous because he’d singled me out to Ms. Linda as having talent and promise.

We had to move the next year, though, because Dad got an offer from Uncle Van to have his own dealership. I got my first slip that year, when I was twelve, which made my mother cry. I wore it under a dress for our going-away party. I also wore her sandals, which were a half size too big, but it was fine because I took them off to dance around in the backyard as the boys played football. At one point, I said, “Well, I can do this,” and grand jeté’d through their game.

We left Indian Mound Road and the house with the empty carpeted room off the dining room area. John Lennon had died the previous December, and I’d been glad to be alone in that house to listen to his song “Woman,” which played repeatedly on the radio. I cried without any knowledge of what a woman was, but I’d seen pictures of Yoko Ono and she was almost an adjective in my mind for someone who was different. Blondie’s song “Rapture”—“I said don’t stop, to punk rock.” We left Monroe in a packed station wagon, as two dogs humped in our neighbor, Maw Maw’s yard. I was holding our new poodle, B.B., and Dad said “Cover B.B.’s eyes! Don’t look at that” and we laughed as we cried, as I tried to cover her eyes.

We were moving to Laurel, Mississippi, a quaint, old Southern town, much smaller than Monroe, that still had the provincial Gone with the Wind–ness of the Old South niceties, where “Don’t you look cute” sounded to me like that was all that was expected. It was a town where you had to belong to a church, and being Catholic was weird to other Christians because we worshipped Mary, drank wine that we called “the blood of Jesus,” and also ate his body in the form of a wafer cracker. People in the town took their religion so seriously that there was an ongoing “my church is better than your church” drama. There were forty-one Baptist churches, and the two most popular ones, Highland and First Baptist, had competing bumper stickers. “I found it at Highland,” and, touché, “I never lost it at First Baptist.” Found what? Lost what, exactly? In seventh grade, there was a rumor that the magnetic strip on the back of credit cards was a code written by the devil. The girl that told us this was freaked out and pleaded with us to tell our parents not to use credit cards because they would go to hell. She had no idea then that she was a burgeoning anticapitalist—now she was just a homewrecker.

My dad took my brother to a KKK meeting when we moved to Laurel because he wanted to show Chris how crazy it was. I had wanted to see the idiots, as my father called them, but I was a girl and he didn’t want me there. I was a ballerina at this point and this town was breaking my vibe.

One of the churches in town had a Christmas pageant, and God flew in a carpenter/actor from Florida to play Jesus. The minister’s wife ran away with him after the show, so she got saved finally. She found it, and was no longer lost. I think as the story goes they lived happily ever after in the hair salon they shared together in Florida.

That summer—the summer we moved—Tanju Tuzer suggested I apply for a six-week summer ballet class with the University of North Carolina School of the Arts ballet company. I got in and had the time of my life the following summer. I auditioned to enroll as a full-time student but didn’t make the cut. My dad knew I’d be devastated so he called the dean to ask him what he should tell me and he said, “Tell her she’s an actress.” I think the dean was called Dean Irby an

d he said I’d almost gotten in based on my personality. When Dad told me this, I was shy about these ambitions because I didn’t want to upstage my family, and being a professional actress, I invariably would. My dad was the star of the show, always. He’d do things like place a fart machine under the seats at check-in at the airport and we’d wait for reactions when it sounded off. His performances were nonstop. He’d introduce himself afterwards and make small talk with strangers—sometimes they laughed and sometimes they didn’t.

I’d go back to Laurel, where I starred in Little House on the Prairie in my living room, opposite the television set. I’d seen many episodes, and when Melissa Gilbert cried, I cried along with her. I could almost guess the dialogue. My mom and I loved to watch Mommie Dearest together. We got the “camp” of it and would imitate it for fun. “Clean up this mess, Christina!” “That’s just like my mother!” she’d say, and we’d laugh.

I liked when my parents would go out on a date so I could be alone and put on this black lace turn-of-the-century dress that I’d gotten in a secondhand store in New Orleans. It was like something Madame Defarge, from A Tale of Two Cities, would wear, the knitting old crone in her rocker who knew all the details of the tragedy. Or Miss Havisham from Great Expectations, another great part. The dress had holes in it and smelled like cat urine. I washed it in my bathroom sink, which made the water turn brown, and the smell never left, but I wore it anyway and played depressing music on my record player and cried. That was my idea of fun. I’d put ice in the sink to wash my face and then get into bed to read or write a letter, or watch Pee-wee’s Playhouse on a recorded VHS tape in the TV room. I have no idea what happened to that dress.

You're on an Airplane

You're on an Airplane